Path based routing can be an extremely useful feature. It enables you to serve a single page app and an API on the same domain. This can often be helpful when starting a project, but don’t want to handle things like cross-origin resource sharing. In a recent project, I wanted to split traffic between a static site hosted on GitHub (or S3) and an API running in the cluster. In this post, I’ll demonstrate some less common approaches to path based routing using Kubernetes resources.

Kubernetes supports routing HTTP requests via an Ingress resource.

This directs processes known as ingress controllers to route communication for a host / path pair to a given backend service.

Services represent to a collection of backend pods, which are mapped through Endpoints (soon to be EndpointSlices).

They come in several variations: ClusterIP (default), NodePort, LoadBalancer, ExternalName, and Headless.

In this post, we will focus two, ClusterIP and ExternalName.

To continue the spirit of keeping posts lighter on code, all configuration used today is available on GitHub.

It provides a minimal footprint to show how to connect the parts together.

Some files require bringing your own values (such as a DOMAIN, REGION or BUCKET).

Before getting into the ingress, let’s deploy an api-service stub.

kubectl apply -f api-service.yamlThis can act as a placeholder for your real API if you don’t yet have one. This service will handle all API requests.

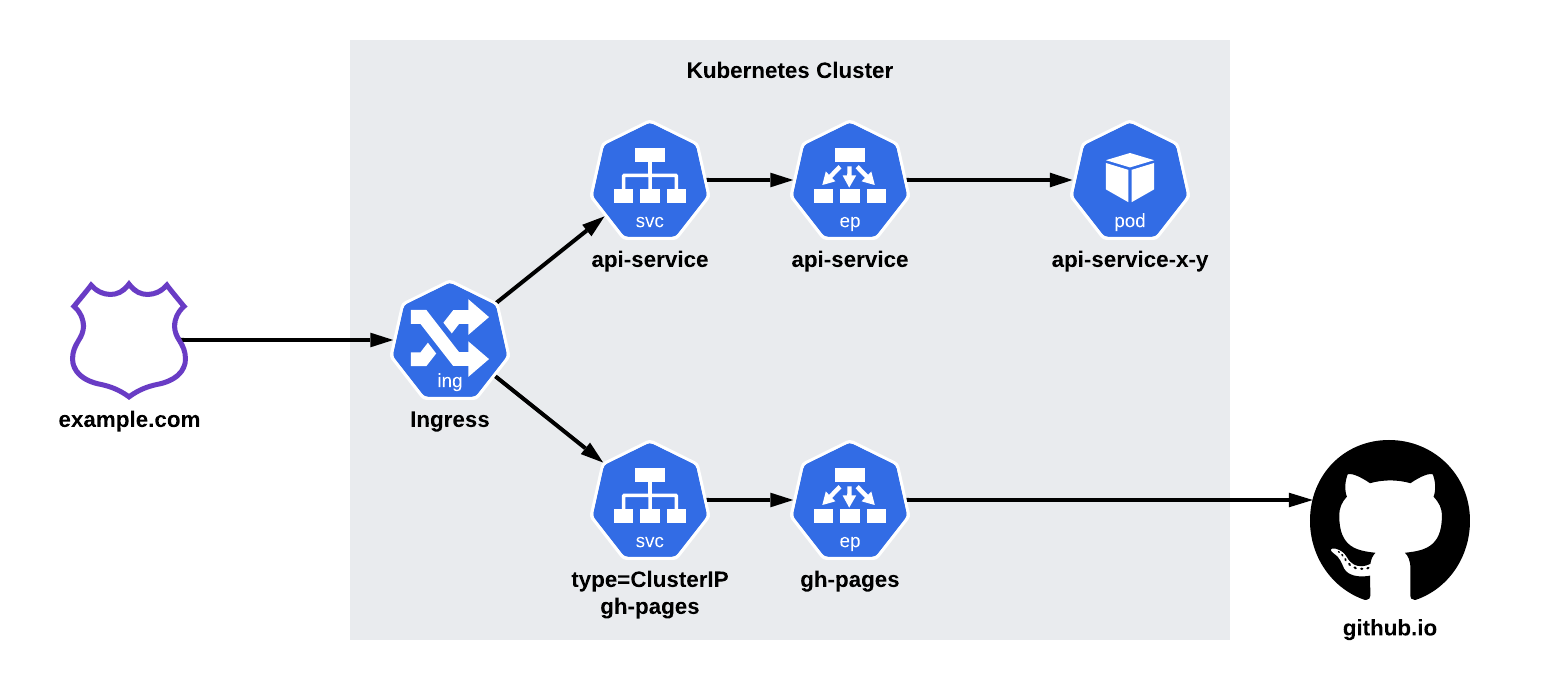

Manually configured ClusterIP

First, I will demonstrate how to manually configure a ClusterIP service to point to GitHub pages.

Using an ingress definition, we will split traffic between two backends.

Requests to /api/ will be sent to an api-service backend.

All other requests will be routed to GitHub pages.

This is shown in the diagram below.

First, we’ll create the gh-pages service.

This file sets up the service, and it’s associated endpoint.

The IP addresses for the endpoint can be obtained by looking up the nameservers for github.io.

kubectl apply -f gh-pages-service.yamlOnce created, you will have a gh-pages service.

This allows us to point our ingress definition directly at GitHub pages.

Applying our ingress configuration, will allow traffic to flow seamlessly between the two systems.

kubectl apply -f gh-pages-ingress.yamlUsing a CNAME

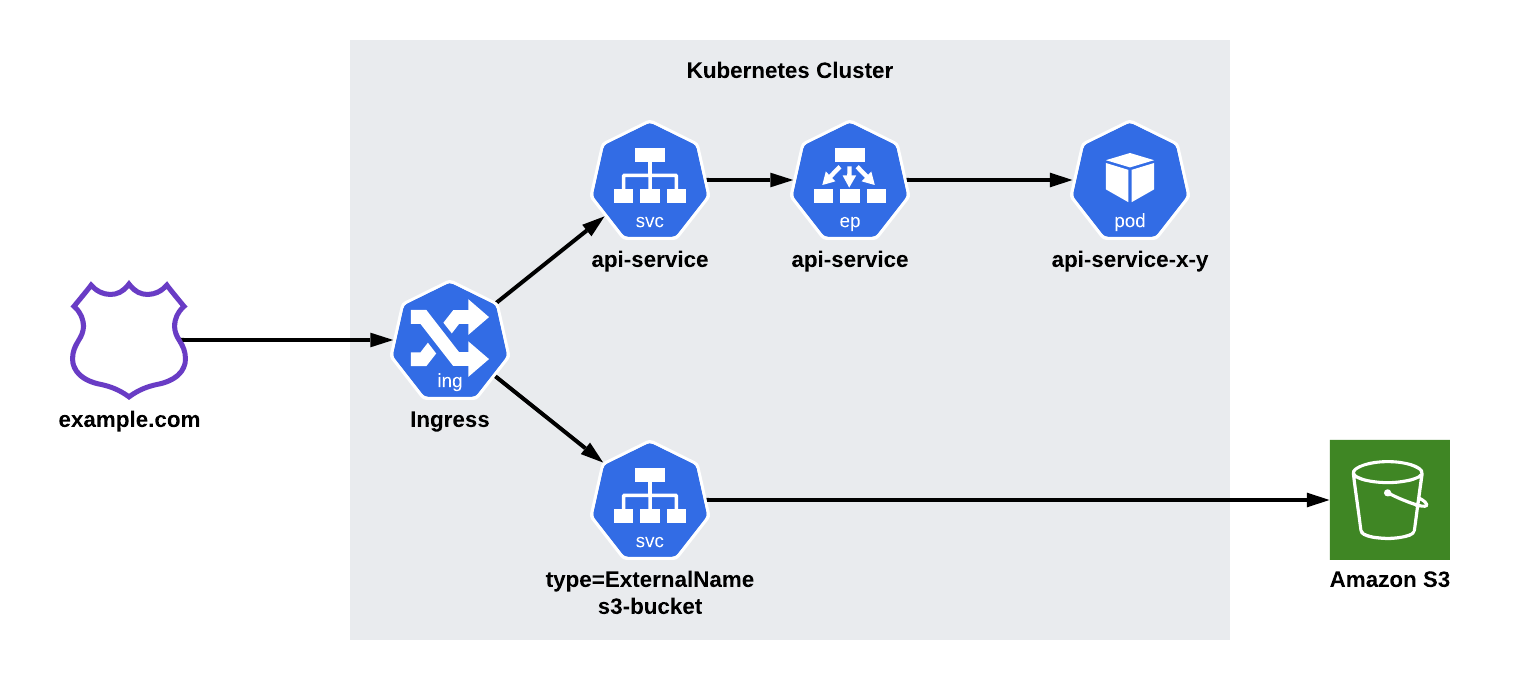

Next, I will demonstrate how an ExternalName can be used to point to an S3 bucket.

We will be using a similar ingress setup (as seen below).

This time, we will use an ExternalName service instead of a ClusterIP.

ExternalNames are more or less a DNS CNAME.

They allow us to reference another host address that’s serving our content.

kubectl apply -f s3-bucket-service.yamlOnce created, you will have an s3-bucket service.

This allows us to point our ingress definition directly at the S3 backend.

Similarly, we can deploy the ingress and have communication flow seamlessly between the systems.

kubectl apply -f s3-bucket-ingress.yamlTips and Tricks

Use sparingly

For small numbers of paths, path based routing is fine. If you find that you’re spawning more and more routes, managing them can become difficult.

Backends should serve on the paths they’re listening on

Having application logic that binds to a specific path can often be clunky for developers. Subdomains tradeoff the complexity of path management (from an development AND operational standpoint) for the complexity of CORS.

Exercise

A docker-registry is a great example of a service that can be deployed in such a manner.

The registry only serves requests on /v2/, making it an easy target.

docker-auth can be added to lock down access.

It only needs access to your authentication path (/auth, /google_auth, or /github_auth).

Finally, you can throw an open source UI on the / to give visitors an easy to use UI.

For a starting point, take a look at my previous blog post on my [docker registry setup]({{< ref “/blog/2020-11-03-registry-123.md” >}}).